- State weighs buyouts, prohibiting new development, tax hikes

- Policy could become template for climate adaptation nationwide

Louisiana is finalizing a plan to move thousands of people from areas threatened by the rising Gulf of Mexico, effectively declaring uninhabitable a coastal area larger than Delaware.

“Not everybody is going to live where they are now and continue their way of life,” said Mathew Sanders, the state official in charge of the program, which has the backing of Governor John Bel Edwards. “And that is an emotional, and terrible, reality to face.”

Months of community meetings on the program wrapped up this week.

The draft plan, a portion of which was obtained by Bloomberg News, is part of a state initiative funded by the federal government to help Louisiana plan for the effects of coastal erosion. That erosion is happening faster in Louisiana than anywhere in the U.S., due to a mix of rising seas and sinking land caused in part by oil and gas extraction. State officials say they hope the program, called Louisiana Strategic Adaptations for Future Environments, or LA SAFE, becomes a model for coastal areas around the country and the world threatened by climate change.

While the state hasn’t come up with a cost estimate, the buyouts and resettlement could add up to billions of dollars. The federal grant for the initial phase cost $40 million.

The idea hasn’t gone over well with all the people it’s supposed to help, some of whom want the government to do more to protect their communities instead of abandoning them.

“Are we doing every single damn thing we can? I don’t think we are,” Richie Blink, 31, said over a bowl of gumbo in Empire, a town 60 miles south of New Orleans on the bank of the Mississippi River. He paused, then said he didn’t mean to get worked up. “This stuff wears you out emotionally.”

Empire lost half its population after Hurricane Katrina, and now has fewer than 1,000 people. Blink, a community organizer for the National Wildlife Federation, said he understands the dilemma political leaders face, but wishes they would do more to keep the area habitable longer.

Empire’s harbor has a flood gate to protect the boats inside from extreme weather. “When I was a kid, it was a big deal to see the flood gates closed,” said Blink. This year, he said, those gates were closed for 100 days.

Sanders is working to complete the plan by early next year, at which point it will be up to federal, state and local officials to decide if they will implement it. Edwards, the Democratic governor, announced his support for the program in March. If he backs its recommendations, the state could create a buyout program or eliminate the homestead exemption for homes in high-risk areas, which would mean higher property taxes for many residents.

In a statement, the governor’s office said he is “following the progress being made by the LA SAFE team intently and looking for ways to build upon their success as we determine the next steps for the program.”

Under the proposal, commercial development would still be allowed, but developers would need to put up bonds to pay for those buildings’ eventual demolition.

Rob Moore, a flood policy expert at the Natural Resources Defense Council in Chicago, said that if the state goes ahead with the plan, “then every coastal state in the country should be asking themselves, ‘If Louisiana can do this, why aren’t we?’”

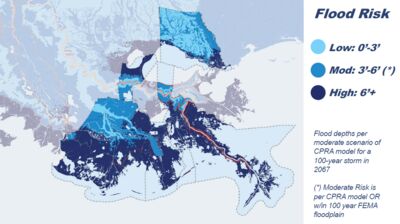

The LA SAFE program defines as “high risk” land where, five decades from now, the expected depth of a 100-year flood will reach more than six feet. According to data provided by state officials, 94 percent of the land in Plaquemines Parish, which includes Empire, falls into that category.

Across the six coastal parishes covered by the LA SAFE program, more than 59,000 people live in those high-risk areas. The proposed buyouts and restrictions on future development would only apply to the parts of that land that aren’t protected by levees, and the state isn’t sure how many that may be.

Another town on the wrong side of the state’s risk map is Leeville, a cluster of houses and trailer homes west of Empire that state officials say will soon be underwater. On a recent afternoon, Opie Griffin stood on the front deck of his family’s gas station and restaurant and wondered what he’s supposed to do then.

“There’s no way they can protect this,” Griffin said, sweeping his hand out over what’s left of the town, the bayou seeping in from all sides. “I see more and more water every year." He put the store up on stilts, perched 16 feet in the air, after Hurricane Gustav blew through in 2008. Now his parking lot floods nearly every day. “Nothing I could do, except come to work on a boat.”

However untenable Leeville becomes, however, Griffin is more worried about what’s waiting for him somewhere else. “I’m almost forty. Do I want to start a whole new chapter in my life?” he asked. “Where do you want me to go?”

No comments:

Post a Comment