Here's a good piece looking at snow fall, how its changing, and whether it will be sufficient to provide ample water to the southwest of the US:

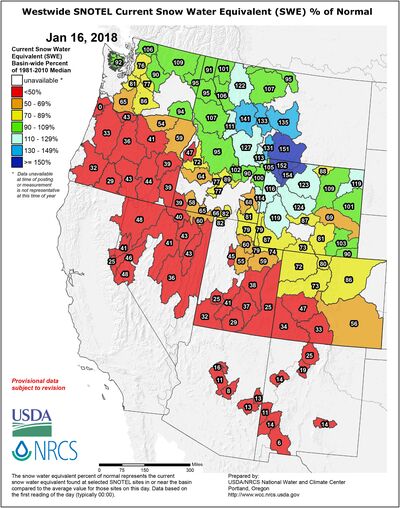

Snowpack is 50 percent lower than the average at this point in the winter at dozens of basins in the region. It’s a major concern in a region with a growing population where water supplies are often pushed to their limits, even in good years. In addition to fueling the West's winter tourism industry, the snow provides a steady supply of water for the Colorado River, which serves 40 million people spread from Denver to Los Angeles.

The problem is not just a lack of snow, but changes in how it is falling and melting. Think of the snowpack as a natural reservoir. During the winter, it freezes in place. When temperatures rise in the spring, the water within is released gradually, filling reservoirs through the rest of the year. That pattern is fracturing around the world. A studyreleased Wednesday by the University of Potsdam also found less available water from snowpack in High Mountain Asia from 1987 to 2009.

In the western U.S., the snow line is receding to higher elevations—typically above 8,000 feet. Below that line, rain is often falling instead of snow, meaning less precipitation is stored in the snowpack. A big storm might send water to reservoirs, but many pools weren’t built to hold a deluge of rain. As a result, they often have to release the water to avoid flooding.

Without predictable snowpack melts, “it reduces reliability on the supply side,” said Demetri Polyzos, a senior engineer for the Metropolitan Water District, the wholesale water agency for Southern California.

There have been bad starts to the snow season before, and climatologists say it’s too early to rule out the possibility that the Western snowpack will bounce back. But even if it does return to average—or above average—levels, researchers said it is unlikely that critical waterways like the Colorado River would get their normal runoff.

“As it warms, you get less runoff,” said Jonathan Overpeck, a climate scientist at the University of Michigan who co-authored the Colorado River drought paper with Udall.

The short-term effects may be manageable. Because 2017 was a wet year, most reservoirs have enough stored water to satiate municipal and agricultural demand through even a dry, hot summer. But water managers still need to respond to the long-term threat.

Western snowpack could decrease by an average of 60 percent over the next 30 years due to anthropogenic warming and natural climate trends, according to an article published last year in Nature.

Climate change will require a coordinated effort in how vital water supplies such as the Colorado River are distributed. Southern California, for instance, has diversified its portfolio with local supplies (desalination plants, recycling water and adding groundwater storage), invested in infrastructure and urged conservation. Arizona, California and Nevada are in the process of negotiating a drought contingency plan to reduce the burden on Lake Mead, the reservoir behind the Hoover Dam that has dropped to 39 percent of capacity.

Pat Mulroy, a Brookings Institution senior fellow known as the “water czar” for her blunt assessments as head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, said the drought plan is but one arrow in a quiver, not a silver bullet.

"For water managers in the West, it means if there has ever been a time for partnership and creative solutions, that time has come,” Mulroy said. “The time to dance around it is over.

No comments:

Post a Comment